Did you know the average European eats around 50 kilograms of bread each year? That’s the equivalent of 3–4 slices a day.(1) And that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Bread (especially wholegrain) can be a nutritious choice: it’s packed with fibre for a healthy gut, along with essential micronutrients like B vitamins, zinc, iron, and magnesium.(1) But are some breads better for us than others?

Lately, one type has been getting a lot of attention: fermented bread. You might have heard of sourdough or seen chewy, tangy “artisan” loaves at your local bakery. But what actually makes them different from standard supermarket or bakery bread? And are they really better for your health? In this article, we’ll explore the story behind fermented bread, why many people find it easier to digest, and how to spot authentic loaves.

What makes bread “fermented”?

At its simplest, bread is just flour, water, and something that makes it rise, such as instant yeast or wild yeast. There are, however, a few different processes that can take place along the way.

Chorleywood bread process

Most supermarket bread is made using the “Chorleywood bread process.” This method uses quick-acting commercial yeast to get the bread to rise, along with extra ingredients like preservatives and emulsifiers.2

Machinery does the mixing, and the instant yeast quickly produces carbon dioxide that puffs up the dough in just a couple of hours. The result is soft, predictable bread with a mild flavour that can be sliced neatly and packaged for sale.

Ultra-processed bread?

Preservatives are ingredients that slow down mould, helping bread last longer. Emulsifiers are used to keep the texture soft and even. Because of these extra ingredients, most supermarket bread is classed as an ultra-processed food (UPF).

That doesn’t mean it’s strictly “bad” for you — but it has had a few things added to it. Choosing wholegrain versions still gives you fibre, vitamins, and minerals that are good for your health. So if you prefer the taste (or price) of supermarket bread, you don’t have to give it up!

Fermented bread

Fermented bread, also known as sourdough, relies on wild yeasts and bacteria naturally present in flour and the air to ferment the dough.

Fermentation might sound complicated, but it is simply the natural process where tiny living organisms like yeast and bacteria break down sugars in the dough. These microbes release carbon dioxide, which makes the dough rise, and organic acids, which give sourdough its characteristic flavour.

Fermented dough usually takes much longer to rise than classic supermarket loaves, often hours or even days. It can be kneaded by hand or with machines. What’s essential is the wild microbes rather than only instant yeast, which gives the bread its special flavour and texture.

Fermented bread is nothing new.

Bread made with natural fermentation might be getting more popular, but it isn’t a modern trend. Archaeological evidence shows people were baking fermented bread more than 8,500 years ago.3 What we now call ‘sourdough’ is a modern version of a very old tradition. It begins with a “starter”.

What’s a sourdough starter?

A starter is a mix of flour and water. This mix captures and multiplies wild yeasts and bacteria. These are the microbes which will ferment the dough, eating sugars in the flour and producing gases that make the bread rise, plus acids that give it a tangy flavour.

Even though we often think of bacteria in food as harmful, the microbes in a sourdough starter are different. These bacteria are mostly lactic acid bacteria, the same kind that make yoghurt and sauerkraut safe to eat. They make the dough acidic, creating an environment where most harmful microbes can’t survive. That’s why sourdough tastes a bit vinegary.

The starter is just the beginning: when you mix it with more flour and water to make a loaf, the entire dough ferments. The amount of time that fermentation takes place can drastically change the health benefits and taste of the final loaf.

Did you know?

Some starters have been kept alive for decades, or even centuries. Even if they dry out or go unused for a long time, they can be “woken up” again by feeding them fresh flour and water, connecting bakers across generations.4

Why does the length of fermentation matter?

Sourdough breads all contain wild microbes to make them ferment. But some ferment longer than others:

Long fermentation (12–24+ hours)8 9 10

- Dough rises slowly, creating complex flavours and a chewy, tangy texture.

- Microbes break down more of the bread’s carbohydrates and gluten, making it easier on the stomach.

- Usually made at home or in artisanal bakeries with just flour, water, salt, and starter.

- Produces an “open crumb” with larger, irregular holes.

Short fermentation (a few hours)11

- Dough rises quickly, sometimes with added commercial yeast as well as the wild microbes.

- Flavour is milder and the texture softer.

- Many supermarket “sourdough-style” breads have a shorter fermentation time than bakery or homemade sourdough.

- Shorter fermentation means less breakdown of carbohydrates and gluten, so it can be harder to digest.

- Crumb is tighter, meaning smaller, more regular air holes.

Safety note: Long-fermented sourdough may be easier to digest for people with mild gluten sensitivity, but it is not safe for those with a gluten allergy or celiac disease. Some gluten-free sourdoughs do exist, using flours like rice, buckwheat, millet, or sorghum.9 These gluten-free versions have a different taste and texture from classic sourdough.

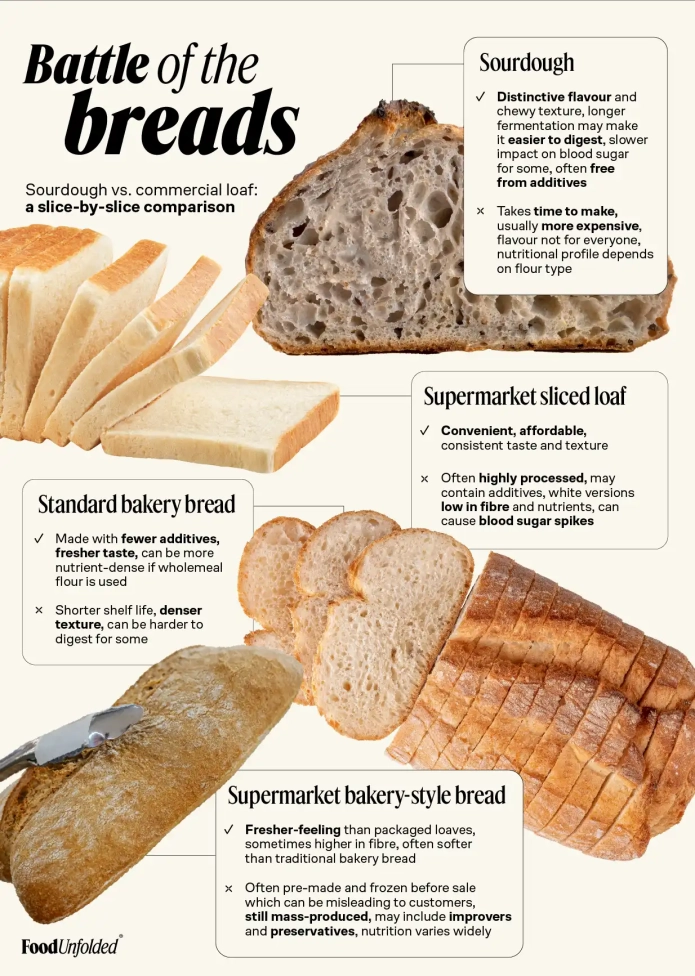

Pros and cons of different breads

Bread is one of the world’s oldest staples, but not all loaves are made the same way. From factory-sliced to rustic sourdoughs, the way bread is produced affects its taste, texture, and nutrition:5 6 7

Did you know? German people eat 80kg of bread per year on average. That’s around seven slices a day, and it’s the most of any European country.1

How to spot the real deal

In many countries, there’s no strict legal definition of “sourdough,” so manufacturers can market bread as “sourdough-style” even if it hasn’t gone through the traditional process.12 With many people willing to pay more, clever mimics have popped up. They may look or taste similar, but often lack the digestive benefits of real, long-fermented sourdough.

Here’s how to make sure you’re buying real fermented bread:

- Check the ingredients: real sourdough usually lists only flour, water, salt, and sometimes “starter.” If the ingredients aren’t listed, don’t worry. In EU countries, food sellers are legally required to tell you what’s in their bread if you ask. Or, if you prefer, you can often check the details on their websites.

- Look at texture and flavour: authentic sourdough should be chewy, slightly tangy, and have an “irregular crumb”, meaning the little air holes will be a slightly different size. Too soft or “perfectly” uniform? That’s a red flag.

Read labelling carefully: terms like “granary,” “farmhouse,” or “multigrain” describe ingredients, not fermentation.13 14

Knowing how to spot real sourdough isn’t just about getting the taste or texture you expect: it also matters for your gut. Long-fermented bread allows the microbes in the starter to do their work, breaking down some of the gluten and carbohydrates that can cause bloating or discomfort. That’s why digestibility is often better with true sourdough than with “sourdough-style” or industrial loaves.

Digestibility and gut health: what does science say?

Our gut is often called our “second brain” because it communicates constantly with our body, influencing mood, energy, and overall well-being.15 A healthy gut supports digestion, immunity, and even mental health, while an unhappy gut can leave us feeling bloated, tired, or irritable.16 17 18

Find out more in: “Good mood food: the link between what you eat and how you feel”

Let’s take a closer look at how sourdough can be one piece of the jigsaw puzzle for a healthy gut.

FODMAPs: why some bread causes bloating

FODMAPs are certain types of natural sugars found in wheat and some other foods. Our bodies don’t always break them down fully in the small intestine, so they can travel to the large intestine, where they ferment. This process produces gas, which for some people can lead to bloating, discomfort and irritation in the bowel.19

Here’s where sourdough is so clever: during its long fermentation, the microbes in the starter get to work first, breaking down many of these sugars outside your body. That means by the time you eat the bread, there’s less work for your own gut microbes to do. With less “food” left over for them, your stomach is less likely to feel gassy or bloated.20

Sourdough isn’t a perfect solution…

It’s worth remembering that gut health isn’t about finding one magic food. It’s the result of lots of little choices made consistently over time.

Eating more fibre, staying hydrated, chewing food thoroughly, and eating fermented foods like yoghurt, sauerkraut, or sourdough all contribute to a balanced gut microbiome.21 It’s also about what you choose not to eat too much of, such as too many fatty foods, ultra-processed foods, or alcohol.21

What about gluten?

Fermentation also works on gluten, the main protein in wheat.

The microbes in sourdough partly break it down during the long rise, which can make the bread gentler on the stomach for people who are sensitive to gluten. It’s important to note, though, that this doesn’t remove gluten completely. Traditional sourdough is still not safe for people with celiac disease or a gluten allergy. (Gluten-free varieties which use different types of flour do exist, but they are hard to find).

The microbiome: what’s really going on with friendly bacteria?

Good bacteria (aka probiotics) are important for a healthy gut. Foods like sauerkraut, kimchi, and live yoghurt are full of these bacteria, which can survive and help your digestive system. Sourdough is a bit different. The good bacteria and wild yeasts in sourdough help the dough rise and ferment, but they don’t survive the heat of baking.22 That means sourdough doesn’t give you probiotics in the same way yoghurt does.

But sourdough still helps your gut in another way. While it ferments, the microbes break down tricky parts of wheat, like gluten and certain sugars (FODMAPs), so your body can absorb the nutrients more easily. They also make natural acids that help your gut stay a little more acidic, which is good for the helpful bacteria and not so friendly for the harmful ones. These acids also slow down how quickly sugar enters your blood, which is gentler on your system.

So it’s not the bacteria themselves that help your gut, but the work they do while fermenting and the acids they leave behind that make sourdough easier to digest and kinder on your blood sugar.

Fermented bread and sustainability

Before we finish, let’s take a moment to think about fermented bread and sustainability. Is sourdough better for the environment than supermarket bread? Not necessarily. You can make arguments for each having benefits:

Environmental benefits of fermented (sourdough) bread:

- Naturally fermented bread can stay fresh longer than quick homemade loaves, reducing household waste.

- Baking with traditional methods preserves centuries-old techniques and local knowledge.

- Choosing sourdough from local bakeries supports local producers and mindful consumption, buying only what you need.

Environmental benefits of industrial (supermarket) bread:

- Large-scale bakeries can bake many loaves at once, which can be more energy-efficient than multiple small ovens.

- Additives can lengthen shelf life, reducing household spoilage and waste.

- Centralised production can sometimes lower transport inefficiencies compared with many small producers.

It’s more important to think about what’s sustainable for you: what you can afford, what tastes good, and what you are less likely to waste. Both sourdough and supermarket bread can be sliced and frozen to pop in the toaster later, helping reduce waste no matter which type you choose.

It's all about balance

Sourdough offers a rich taste, digestive benefits, and a link to traditional baking methods. But it’s not a golden ticket to good health. Wholegrain bread is also rich in fibre and nutrients, so it’s a perfectly good choice for people who prefer the taste or price tag of supermarket loaves.

Whether you buy from a supermarket, a trusted bakery or bake at home, fermented bread can be a delicious, healthy, and sustainable addition to your diet. But the most important thing is choosing nutritious food that you can afford and you enjoy: fermented or not.