Imagine you’re walking past the meat aisle at your local supermarket, eyeing the usual cuts of beef and chicken. Only this time, nestled between them is something different. It looks like meat, smells like meat, even cooks like meat. But it didn’t come from a slaughterhouse. In fact, no animals were harmed in making the product.

You’ve discovered a new kind of food: cultivated meat.

What is cultivated meat?

Cultivated meat is an alternative to the meat we’ve been eating throughout human history. But here’s the thing: it’s still real meat. It’s the same stuff you’d get from a cow or a chicken. The big difference? Cultivated meat doesn’t involve killing animals.

So where does it come from?

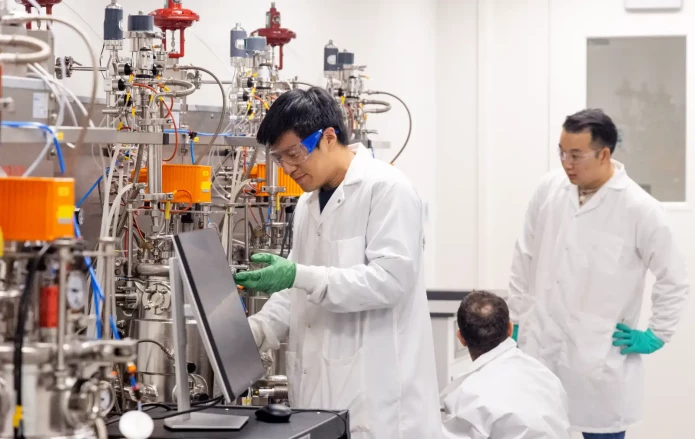

Also known as ‘cultured meat’, cultivated meat is grown from tiny animal cells in a lab. Imagine brewing meat instead of beer. Thanks to scientific advances, it’s becoming possible to grow these cells outside of an animal’s body – in a process called ‘cellular agriculture’.

You can’t buy cultivated meat for human consumption in Europe just yet. Though several companies have applied for approval to sell it in the EU, Switzerland, and the UK.1 2 If you happen to be in Singapore, the USA, or Australia, then you can already find a very limited number of chicken and quail products.3 4

So, why invent this at all? In theory, cultivated meat could offer a healthy and sustainable way to produce meat. It could tackle some of the environmental issues linked with animal production and the health concerns linked with processed meats. More on those later!

But there’s still a long journey ahead before you’re likely to see it sold on a large scale globally.

How cultivated meat is made

To make cultivated meat, scientists begin by taking tiny samples from a real animal, like a cow. These samples contain special “starter” cells called stem cells, which are grown in a lab into the same meat you would find in beef steak, chicken breast, or other meat products.

Science class: how stem cells ‘graduate’ into cultivated meat:

Think of stem cells like students with big potential. They look and behave in a similar way. At first, they’re undecided on their futures. They could become many things: a doctor, a chef, or an athlete. But eventually, they specialise.

In the same way, stem cells inside animals begin as unspecialised and then “differentiate” into specific types of cells – like muscle, blood or fat – which make up the meat we eat.

But how do you grow meat outside of a body? Here’s how it works in 4 steps:

1. It starts with a tiny muscle sample

Scientists, often working with farmers, collect a tiny sample from an animal. That might be from a muscular part of a cow, or even from an egg before it develops into a chicken. The all-important stem cells are isolated from the rest of the sample.

2. The cells go into a bioreactor – a bit like an incubator

This machine keeps them at just the right temperature and provides oxygen. The cells are also bathed in a nutrient-rich ‘soup’ containing everything they need to grow – vitamins, proteins, and more.

3. Cells grow into muscle and fat

Over time, scientists tweak the conditions in the bioreactor so that the cells mature into different types of tissue, including muscle and fat. Sometimes, a support structure is used to shape them into familiar forms, like a typical steak you see in a restaurant.

4. The result: cultivated meat

Once ready, the liquid is drained off and what’s left is meat – ready to be cooked, served, or combined with other ingredients. The whole process is expected to take 2–8 weeks, with less structured products like minced meats being quicker than products with various textures like a steak.5

Did you know? In the early days, cultivated meat was often grown in a liquid called fetal bovine serum, a by-product of the meat industry. As this defeated the whole point of “slaughter-free” meat it is being phased out.6 7

What are the potential benefits of cultivated meat?

There are big challenges with how we currently produce meat. Globally, meat consumption has more than tripled in the last 50 years.8As countries get richer, meat consumption tends to increase. The growth has been particularly dramatic in Asia, as large nations like China and India have developed economically in recent decades. In Europe, the change has not been so dramatic, but still significant – the average person ate 79 kg of meat in 2022, compared to 49 kg in 1961.

Animal farming accounts for 20% of all human-related greenhouse gas emissions, making it a major driver of climate change.9 Beef has a particularly high environmental footprint, mainly from methane released by cows and emissions from growing animal feed. Producing just 1 kilogram of beef creates about 99 kilograms of greenhouse gases – similar to driving from Paris to Zurich in a petrol car.10 11 To produce your 1 kg of beef (2-3 steaks, or 6-7 burgers) also needs around 1,451 litres of water – around 10 bathtubs.12

Diets high in red and processed meats have also been linked to health conditions, including cancers and heart disease. It is not that meat is always unhealthy. In fact, lean meats can be a healthy source of protein to support growth and healing. Animal products are also a good source of nutrients like iron, vitamin B12, and zinc. But your risk of health issues can increase if you regularly eat processed meats, like salami, sausages and canned meats. These have been altered through salting, curing, or chemical additives.

Here are some of the potential benefits of cultivated meat:

| PEOPLE | PLANET |

Slaughter-free: A new option for those who want to eat meat without harming animals. Tailored nutrition: In future, it might be possible to adjust the fat or nutrient content to suit different diets. | Less polluting: Cultivated meat could cause significantly less air pollution than conventional meat production. Fewer resources needed: It could be produced with much less land. Less planet-warming? Compared with conventional beef, cultivated beef could cut some of the greenhouse gas emissions. For instance, the methane emitted by cows, and it could be produced near cities – cutting down on transport.13 But some scientists have disputed the climate benefits of cultivated meat. They point to the high energy use linked with the materials and processes to produce cultivated meat.14 |

Cultivated meat: a new option for your plates

Let’s be clear: cultivated meat isn’t about replacing traditional meat entirely. It’s about offering more choices.

Many of us are becoming more aware of the environmental and ethical impact of our food. Reducing how much meat we eat is one of the most effective ways to shrink our environmental footprint.

We’ve already seen plant-based options take off, take burgers for example. Plant-based burgers made with ingredients like tofu, legumes or fungi, have become popular with both meat eaters and non-meat eaters.

Cultivated meat adds another choice to the table. It’s real meat, made without slaughter and potentially with fewer environmental impacts. But whether you try it is completely up to you.

Don’t get too excited just yet – many challenges remain

We need to think about energy. Mark Post, the scientist behind the first cultivated burger in 2013, said the goal was always to reduce environmental harm.15 But to feed more people, we’d need massive facilities – and those would use a lot of energy. If that energy doesn’t come from renewable sources, the benefits could be wiped out.

Is it ultra-processed? Some people are wary of cultivated meat because we’re also being advised to eat fewer ultra-processed foods. But it depends how we define that term. “Ultra-processed” usually means foods with added sugars, preservatives, and colourings. Think soft drinks, microwave meals, crisps and other packaged snacks.

Cultivated meat is different. It’s made from animal cells – just like conventional meat – but grown in a new way. So, is it ultra-processed just because it’s made in stages in industrial facilities? The debate is still open.16

Maybe it’s too expensive to scale. Another big hurdle is the cost of this innovation. The first lab-grown burger in 2013 cost over $300,000 and took two years to make. That sounds wild – but new technologies often start out expensive. Remember the first computers? An IBM 7090 from 1959 filled a room, cost millions of dollars, yet still had a fraction of the computing power of the smartphone in your pocket.

By 2030, production costs for cultivated meat could be as low as €9 per kg ($US5/pound).17 But some experts are sceptical.

Vaclav Smil, a Czech-Canadian scientist and policy analyst, calculated what it would take to replace just one per cent of the world’s meat with cultivated meat. He found we’d need a hundred times the bioreactor capacity of the world’s entire pharmaceutical industry.18 Simply put, that is an enormous leap from where we are today.

Then again, at the start of the 20th century, many people said human flight was a fantasy. In 1903, the Wright brothers took off.

The lawyers need to be happy, too. There’s also the legal side. Within the EU, cultivated meat is classed as a “novel food” – an ingredient that wasn’t commonly eaten in Europe before 1997. Companies need approval before they can sell novel foods, which involves rigorous safety and regulatory checks.

Understandably, investors are cautious before approvals are granted.

What your first taste of cultivated meat might look like

Because it’s hard to recreate the tastes and textures of meat, the first available products are likely to be fairly "unstructured", such as mince, nuggets and hamburgers.5 More complicated meat items, such as t-bone steaks, will take longer to reach supermarkets.

Where might you already find it?

Singapore was the first country to approve the sale of cultivated chicken in 2020. In 2022, in the US, the Food and Drug Administration declared cultivated meat safe to eat. To date, products have only been available in a limited number of restaurants. In 2025, the Australian regulator approved the sale of cultured quail products from a Sydney-based startup.4

Europe is moving more cautiously. In July 2023, the Dutch government allowed cultivated meat tastings in controlled settings – the first such step in Europe. In the same year, the Italian government passed a law banning the production, sale or import of cultivated meat or animal feed.

So, if you’re in Europe, your first taste might come via a food event or a fine dining restaurant in specific countries. Over time, products could start appearing on supermarket shelves.

Look out for alternative names:

Companies are likely to address the concerns that cultivated meat is not real meat. Over time, you might see the products advertised under other names like “clean meat,” “cell-based meat,” or just “CM.”20

What are people saying about cultivated meat?

Many people have heard about cultivated meat through documentaries or social media. In Europe, curiosity is growing – even if most people haven’t had the chance to try it yet. Here are some comments from a 2023 EIT Food survey of 95 participants from 16 European countries and Israel.21

“A few years ago I heard about cultivated meat on the internet and in discussions with friends. I can't remember exactly what it was but I thought that it is a really really good idea, even though it would be weird to eat something like that the first time. Still a good idea.” — Koffi, 33, Switzerland

Others are more cautious about how it might taste:

“I have never tried cultivated meat, but as it is still in experimental phase as I am aware about, I think it would taste strange and synthetical,” — Victor, 46, Spain

Adventurous eaters will shape the future of food

Whether or not you try cultivated meat will come down to personal choice. It is one of many new ideas being explored to make healthy and sustainable food more accessible. It will not magically solve everything by itself. But it could become part of a mix of new options. As consumers, our curiosity and choices will help shape what that future looks like.