Have you ever wandered through a local food market? Vendors call out their best prices, the smell of freshly baked bread wafts from a nearby stall, and everywhere you look, there seems to be an abundance of choice. But despite how vibrant and varied markets, shops, and supermarkets may appear, the reality is that we eat far fewer types of food than we used to.

This shift began after World War II, when farming practices changed dramatically. Large machines made it easier to grow vast amounts of the same crops. As a result, we now enjoy access to fresh fruits and vegetables year-round. But this convenience also means that fewer kinds of crops are grown, and there’s less variety in what ends up on our plates.

This decline in crop diversity affects both our health and the health of the planet making it a very important topic. In this article, we’ll explore why crop diversity is disappearing, why it matters, and what we can all do to help protect it.

What is crop diversity?

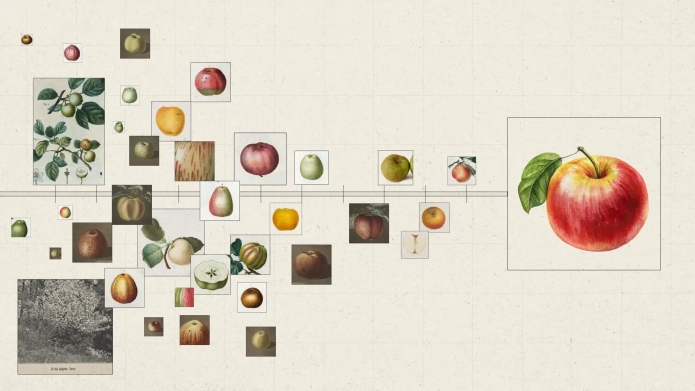

Crop diversity means having many different kinds of plants for food. It’s not just about different fruits and vegetables, but also about different types of the same crop. For example, there are over 7,000 varieties of apples that look, taste, and grow a bit differently.1 However, it’s nearly always the same few apple varieties appearing on European supermarket shelves, such as Pink Lady, Golden Delicious, Gala, or Granny Smith. These are delicious apples that store and transport well, but have you ever heard of Bloody Ploughman, Robston Pippin, or Stinking Bishop?

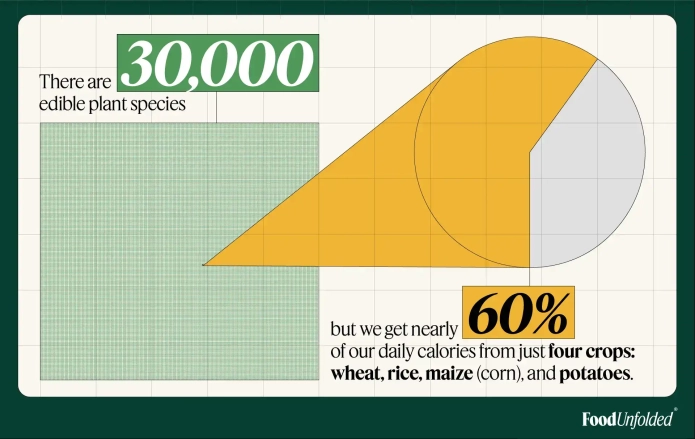

Did you know? There are 30,000 edible plant species, but we get nearly 60% of our daily calories from just four crops: wheat, rice, maize (corn), and potatoes. Think of your favourite staples like bread, pasta, or rice… did any of them show up in your meals today? Maybe even at every meal you had?

It isn’t just funny-sounding apples that are getting forgotten. Almost all crop species have varieties, whether just a few or many thousands:

- As well as the classic Jasmine and Basmati, there are 40,000 different varieties of rice in the world!4 We think of rice as white, but it can also be black, red, or purple.

- Have you heard of the Green Zebra, a green-striped tomato, or the Reisetomate, which looks a bit like a bunch of grapes?56 There are over 10,000 different types of tomatoes out there.7

- There are more than 5,000 kinds of potatoes, including the deep purple Vitelotte and La Ratte, which is known as “the truffle of potatoes” for its rich flavour.8

Bringing crops back to life. All around the world, we’re losing crop diversity. But many farmers are working to protect and revive old varieties. In the UK, farmers are reviving black oats, an ancient grain that supports local wildlife and maintains healthy soil.

Where did all these crop varieties come from?

People didn’t always farm. At first, we survived by hunting animals and gathering wild plants, honey, and eggs. Around 11,000 years ago, people began saving seeds from the plants they liked most.10 Over time, they developed a mix of crops that suited their needs through careful cultivation. Then everything sped up.

As farming became more industrial, we started selecting crops based on what worked best for big farms, long-distance transport, and supermarket shelves. We chose fruits and vegetables that looked neat and uniform, stayed fresh for longer, ripened at the same time, and could survive being shipped worldwide.11 12

Uniformity vs variety

Have you ever looked closely at the fruits and vegetables in a supermarket and noticed they almost all look the same—same size, same colour, and perfect shape? This is partly because farmers and companies developed crops that grow more uniformly, making them easier to harvest and sell.

In this quest for perfect vegetables that grow fast and sell well, thousands of traditional (heirloom) varieties are being left behind. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation, about 75 percent of global crop diversity was lost between 1900 and 2000.13

This doesn’t always mean these crops have gone extinct, but many have disappeared from supermarkets and farmers’ markets, making them hard to find and eat. Some gardeners can still buy seeds online, while others survive only because families pass them down through generations.

Why does crop diversity matter?

When we lose crop diversity, we lose food options. Here's why that matters:

1. Crop diversity makes us more resilient to climate change

Climate change is making the weather less predictable, which means more floods and droughts. Luckily, species and varieties can cope with different conditions. Some are better in wet weather, and others can survive without much water. This resilience is key for food security in a changing climate.

Instead of losing all the food on a farm to drought, we might just lose one species. This is important for farmers who can only make a good living if they have enough food to sell.14

2. Crop diversity protects food from pests and diseases

Growing lots of different plants helps protect our food from pests and diseases.

If a farm only grows one kind of plant, a disease or pest that likes that plant can wipe out the whole field. But when farmers grow a mix of different crops (or varieties of the same crop), the problem is limited. Some plants might resist the pest, while others might not attract it at all. It’s like building a natural barrier.15 16

3. Crop diversity means better nutrition

Different crops give us different nutrients, and even different varieties of the same crop can offer a unique mix of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. For example, carrots are usually orange, but they also come in colours like purple, yellow, red, and white. Each colour comes with slightly different nutrients. Traditional crop varieties often have more fibre, protein, or micronutrients than the highly selected commercial types in supermarkets.17 18

4. Crop diversity is cultural diversity

Did your grandmother ever use fresh herbs from her garden to make your food taste special? Now imagine those herbs disappearing forever.

Crop diversity isn’t just about farming or food. It’s also about people, stories, and identity. Traditional crops did not appear overnight. They were shaped over thousands of years through care and dedication, seed by seed and season by season. Farmers and gardeners chose the best plants, saved their seeds, and passed them on. When we lose a crop variety, we don’t just lose a plant. We lose the care, knowledge, and wisdom of all those mothers and fathers who tended the soil, tasted the harvest, and their children who carried those seeds into the future. Along with the crops, we lose traditional recipes and ways of cooking that connect us to our history and culture.

Did you know? In Spain, farmers still grow dozens of traditional varieties of wheat called “trigo de secano,” which means dryland wheat. This hardy wheat is grown without irrigation, relying only on natural rainfall, and is well adapted to the dry and tough conditions of the Mediterranean, even in the face of climate change. They are used to make regional breads and pasta, each with its own unique flavour, helping to keep centuries-old food traditions alive and supporting sustainable farming.

What’s being done to bring back food diversity?

The good news is that there are still so many crop varieties to care for, hundreds of thousands of them! All over the world, people are working hard to bring diversity back onto our plates. From farmers to scientists to home gardeners, these efforts will help us stay resilient in the face of climate change.

Let’s look at some projects which are keeping traditional crops alive:

1. Seed banks

Think of seed banks as treasure boxes filled with seeds. They preserve thousands of plant varieties by storing them in secure, cool environments to safeguard them for future generations. A well-known example is the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway. Located deep within a mountain, it keeps duplicate collections of seeds from across the globe, serving as a backup in case original seeds are lost because of conflicts, natural disasters, or the impacts of climate change.21 22

2. Traditional (heirloom) vegetable gardens

All over the world, farmers and gardeners are saving and growing older plant varieties, often called heirlooms. These crops might not look as perfect as supermarket produce, and they sometimes grow a bit slower, but they often taste better, have unique colours and shapes, and are better at coping with local conditions.2324

Did you know? In Campania, southern Italy, farmers still grow the Pomodorino del Piennolo. This is a small, sweet tomato variety that’s been cultivated for centuries on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius. Its unique flavour and long shelf life make it a treasured part of local food culture. If it’s hung in an airy place, it can stay good for months at room temperature!

3. Genetic engineering and plant breeding

Scientists are also using new tools to speed up what farmers have been doing for thousands of years: choosing the best plants and combining them to grow stronger, healthier crops. This is called breeding. Normally, it takes a long time. But with genetic engineering, scientists can now do it faster and more precisely.

For example, if a wild tomato doesn't get sick easily, scientists can find the helpful part of its DNA and add it to a tomato we eat today. This can help farmers grow food with fewer chemicals. But it’s important to use this technology with care. It needs strong safety checks. And we also need to make sure that farmers still have lots of different seeds to choose from. If just a few companies control most of the seeds, it can make it harder for other kinds to survive. Having many types of seeds helps protect food diversity and gives farmers more freedom.27

What can you do for crop diversity?

You don’t need to be a farmer or a scientist to help protect food biodiversity. Here are a few simple ways you can get involved:

- Try something new:

Always reach for Granny Smith apples? Next time, try the smaller Fuji variety. Start small, but make it a habit to switch things up each time you shop – you might be surprised by the different flavours. - Check out a farmers market:

Traditional (heirloom) vegetables might look a bit different. They often have funny shapes, unusual colours, or different sizes. But they taste great and have a story behind them. You can often find them at farmers’ markets where small farmers are selling directly to people. If you don’t see any, ask! Showing you want them helps farmers grow more. - Grow your own from traditional seeds:

You can find heirloom seeds online or through seed-saving groups. Try planting them in pots, window boxes, or a garden if you have one. If space or time is tight, consider joining a community garden where you can share tools, knowledge, and seeds. - Save and share seeds:

Once you’ve grown your traditional crops, save seeds from the healthiest and tastiest plants. It’s a great way to save money and support crop diversity at the same time. You can swap seeds with friends, neighbours, or at local seed exchange events so that other people can enjoy these special varieties too.

Did you know some farms welcome visitors? You can tour local farms that grow old crop varieties, taste rare flavours, and learn more about sustainability in agriculture. Why don’t you see if there’s one near you?

Final thoughts

In this article, we’ve explored what crop diversity is, why it’s disappearing, and why it matters more than ever. We’ve seen how growing just a few types of crops has made our food system more vulnerable (think climate change and pests) and how it’s reduced the variety and nutrients in the food we eat.

But we’ve also seen how crop diversity can be part of a future solution. As scientists and farmers work hard to bring back diversity, and even introduce modern technologies, we now have an opportunity to support their efforts. This doesn’t require radical action, it can start with something as simple as trying a new grain, shopping at a local market, or learning about forgotten foods. Simply staying curious and informed is a good first step towards a more sustainable and healthy future.

References

- The Rice Association. (n.d.). Types of rice.

- Benoit, D. J. (2023). A history of tomatoes. University of Vermont Extension.

- Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. (n.d.). Potato (Solanum tuberosum). Retrieved May 16, 2025, from

- New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station. (n.d.). Tomato varieties. In What to Plant: Tomato Varieties. Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Retrieved June 24, 2025, from

- Stock, J., Maher, L., & Richter, T. (2012). From foraging to farming: The 10,000-year revolution. University of Cambridge

- Alonso, I. O. (2024. A five-course history of our modern food system. FoodUnfolded.

- Bailleau, R. (2023). Is polyculture the key to food security? FoodUnfolded.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2010). Crop biodiversity: Use it or lose it. FAO.

- Cafasso, S. (2020). Crop diversity can buffer the effects of climate change. Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

- Hansen, E. (2024.) Beyond the monoculture: Why we need biodiversity in agriculture. University of Illinois Extension.

- Bhardwaj, R. L., Paliwal, A., & Paliwal, H. P. (2023). An alarming decline in the nutritional quality of foods. Frontiers in Nutrition, 10, 1131507.

- Lyons, G., Dean, G., Tongaiaba, R., Halavatau, S., Nakabuta, K., Lonalona, M., & Susumu, G. (2020). Macro- and micronutrients from traditional food plants could improve nutrition and reduce non-communicable diseases of islanders on atolls in the South Pacific. Plants, 9(8), 942.

- AgRawData. (2024, March 5). Adaptación y rendimiento: Las mejores variedades de trigo para cultivo en secano. AgrawData. Retrieved June 24, 2025, from

- Pérez Picón, M. (2019). Trabajo de fin de máster, Red Andaluza de Semillas, Retrieved June 24, 2025, from

- Colarossi, J. (2025). Keeping seeds alive if the world as we know it ends. The Brink. Boston University.

- Gupta, S. (2025). Cryopreservation is not sci-fi. It may save plants from extinction. Science News.

- Westerfield, B., & Richardson, W. (2024). Heirloom vegetables in the home garden (Circular 1302). University of Georgia Cooperative Extension.

- Jain, S. (2023). 2023 is The International 'Year of Millets' | Here's Why They Matter For Global Food Security. FoodUnfolded.

- Donati, S. (2016, January 14). Sweet tomato from Mt. Vesuvius: Pomodorino del Piennolo. ITALY Magazine. Retrieved June 24, 2025, from

- Parisi, M., Lo Scalzo, R., & Migliori, C. A. (2021). Postharvest quality evolution in long shelf‑life “Vesuviano” tomato landrace. Sustainability, 13(21), 11885.

- Lazzaris, S. (2024). How did GMOs become so controversial? FoodUnfolded

Do you care about thefood system?

Take part in our Annual Survey 2025

Take the survey