Almond milk is marketed as a nutrition-packed, planet-friendly alternative to dairy. But is buying almond milk and other almond products the right thing to do, or has the story we’re being fed been artificially sweetened?

A commonly reported ‘superfood’, almonds are rich in calcium, vitamins and minerals, making almond milk a popular alternative to dairy.1 However, behind the scenes of almonds’ meteoric rise in popularity and production lies a far less positive tale of exploitation and looming environmental disaster.

As of today, there’s around an 80% chance that any almond milk or other almond-based product you consume contains nuts from California’s intensively farmed San Joaquin valley (part of the Great Central Valley). Historically celebrated as the ‘Salad Bowl’, it is now one of America’s most polluted regions because of decades of agrichemical usage. Here, orchards grow in what has been described as a “chemical soup” in order to maintain yields in nutrient void soilscape. This also comes with a host of other lesser-known outcomes, like toxicity amongst farm workers, as well as the death of millions of honeybees trucked in every spring to pollinate the almond orchards.2,3,4

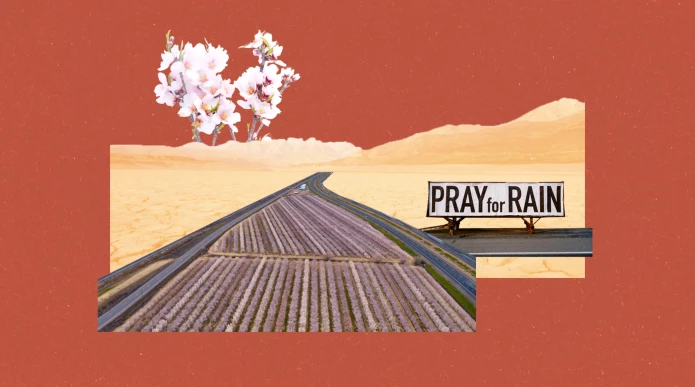

Almond orchards surround an irrigation canal in Shafter, Joaquin Valley California. Desertification has made the valley, once celebrated as America’s ‘Salad bowl’, dependent on shipped water from northern California. (Photo by Ann Johansson/Corbis via Getty Images)

Almonds have traditionally been grown in mixed agricultural settings for centuries. Today, though, industrialised under the aegis of giant food corporations, they’ve become the multi-billion-dollar product of monocultural farming. Monoculture (which sees the cultivation of single species crops over large areas) is antithetical to plant and animal biodiversity, soil health and sensitive environmental management.5

Watch our explainer video on the impacts of monoculture farming

What’s in the chemical soup?

The agrichemicals used to create and maintain successful large scale monocultures are particularly concerning. Artificial fertilisers, herbicides, fungicides and insecticides used to keep farms productive and pest free can leave residues in air, soil and water, as well as accumulating in living things. Many chemicals associated with almond production have come under the microscope; considered potentially, or provenly, toxic to humans and wildlife.2, 6, 7 In Californian almond fields for example, pesticides alone amount to around 16 million kilograms every year.8

Not as sustainable as it seems

It is ironic then, that the global boom in plant milks has been driven by health and sustainability concerns.9, 10 Figures compiled by the United Nations Food & Agricultural Organisation (FAOStat) show global almond production growing from around 1.2 million metric tonnes in 1980 to just over 4 million tonnes in 2020, with the USA by far the most significant producer.11

The steady rise in almond production in the United States has also led to an increase in the number of bee hives being shipped to orchards. Sadly, many beekeepers once able to maintain business producing honey have been forced to go out of business or join the pollination game due to low honey prices globally driven by a combination of cheap, often fraudulent honey imports, and the high demand for pollinators in orchards like those in California’s almond producing region.17

Almond trees also require high amounts of water, putting yet another dent in their claims to be sustainable and planet-friendly - especially when produced in traditionally dry areas like California.

Drought and desertification

Desertification is California’s elephant in the room. With California officially classified as an ‘arid’ state, the current rate of water usage has some experts predicting that it will be completely stripped of water by 2040.12, 21 Adding pressure to the already dire situation, almonds are thirsty trees; each single nut is estimated to take an average of 12 litres of water to produce.22

That’s a lot of water for California’s drought-affected land to stump up for the year-round irrigation of the 1.5 million acres of almond trees in the Great Central Valle, let alone its other food crops. Meeting ever-rising demands for water has resulted in the diversion of rivers (endangering ecosystems) and, even more concerningly, the draining of underground aquifers.13, 14 It has taken thousands of years for these vast natural caverns to build up water reserves, which are now being drained far faster than they can be replenished. Alongside this, California recently experienced its third consecutive year of drought, with parts of the San Joaquin valley so dry that even weeds cannot grow there. With water being drawn from ever-deeper resources, the land level in this increasingly desertified region is now sinking faster during droughts. Some areas of the valley floor are now collapsing at a rate of about 30 cm per year.15

Drought emergencies are now common in Joaquin Valley and some farmers are having to remove crops that require excessive watering due to a shortage of water. Here, a farmer removes 600 acres of their almond orchard to make space for less water-intensive crops - Snelling, California 2021. (Photos by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

“It’s like sending the bees to war”

In a 2020 interview with The Guardian, Nathan Donley of the Tucson-based Center for Biological Diversity commented on almond pollination saying, “It’s like sending the bees to war. Many don’t come back.”16,17

Every February, more than 70% of the USA’s entire stock of commercial honeybee colonies are trucked to California to pollinate almond orchards.4 Around 30% of those colonies will die as a result.16 In North America, 50 billion honeybees (one third of all hives under commercial management) died over the winter of 2018/19, with both direct and related causes traceable to how they were treated in industrialised agriculture.16

Disturbing honeybee colonies over winter, as early as February, can have catastrophic consequences for their welfare, let alone jolting them thousands of miles cross-country on flatbed trucks. Upon arriving in the almond orchards, already-stressed honeybees discover a hostile monoculture soaked in chemicals that yields little nutrition. As early spring temperatures can be too low for them to work safely, they risk dying of chill and damp too. Additionally, scientists have also recorded fatal pests and diseases being transmitted between hives transported between different locations.17, 18

And while there wouldn't be large-scale almond production without the influx of managed honeybees, wild pollinators are suffering too. The combined impact of monoculture farming (loss of habitat, loss of forage and chemical exposure) has led to the destruction of wild pollinator populations, including native solitary bees and bumblebees.20, 24

In absence of wild pollinators killed by the chemicals, almond monoculture conventionally requires the use of domesticated bees that suffer from a lack of nutrients and cold temperatures of this early blossom.

It’s not just about declining honeybee numbers

It’s important to understand that the issue here is not an overall decline in managed honeybee colonies. The use of specialist breeding techniques, such as splitting colonies, compensates for annual losses, so that while overall bee health may be affected, the numbers of hives are kept constant - ensuring a steady income for those renting them out as pollinators.23 In fact United Nations FAOSTAT figures show global hive numbers to have been rising consistently since the 1960’s.11 Rather, it refers to the food industry’s shameful acceptance of millions of healthy bees dying of stress, starvation and poisoning just to get ‘natural’ almond products into the shelves of health food stores and supermarkets.

Going forward

We might all find better alternatives if we follow our consciences. It might be oat milk, which is generally accepted to have the least environmental impact of all the plant-based milk options available. Additionally, there’s light on the horizon for almonds, thanks to ongoing research into more sustainable methods of growing them with ‘agroecological’ land management techniques. By minimising soil disruption (low/no till), adding green manures, and even planting secondary, shade-loving, crops between the trees, producers can minimise damage to the ecosystems while offering a complex range of benefits. Techniques like these can also reduce or eliminate the need for corrosive agrichemical inputs by nurturing healthier trees, suppressing weed growth, and optimising natural water flow.19 Hopefully, this will ultimately lead to less-troubling alternatives for our weekly shopping lists and morning lattes.