Have you had your morning coffee yet? As you pour it into your favourite cup and take that first delicious sip, take a guess at how much water it takes to make it. Five litres? One hundred? Try 250 litres.1 It seems hard to believe, but it’s true. Behind every bite of food and sip of drink we enjoy, there’s a hidden stream of freshwater making it all possible.

We’re often told to save water by turning off taps while brushing our teeth or taking quicker showers. But what many of us don’t realise is that the biggest splash we make with water isn’t in the bathroom. Most of our water usage is invisible. It comes from stuff we buy, like food, clothing, electronics and other goods we find around the house.2 If we include this hidden water, at least half of our overall water consumption comes from what we eat.3

Once we understand how water is linked to our food choices, we can make simple changes with a big impact. With a few tweaks here and there, your water footprint will suddenly look a whole lot friendlier. In this article, we’ll explore what a “water footprint” means, which foods are the thirstiest, and how your everyday food decisions can help prevent water scarcity. Let’s dive in.

What is a water footprint (and why should we care)?

When we talk about the water footprint of food, we mean the total amount of water used to grow, produce, package, and transport our food.4 You can think of it like: how much water did my food have to drink, before it got to my plate?

The fact that our food needs a lot of water doesn’t mean we should give up on other conservation efforts around the house, like only running the washing machine with full loads or fixing leaky taps. And of course, we all need to eat. But it’s worth remembering that different foods use very different amounts of water. We can reduce the amount of water we use and still maintain a healthy diet by making small changes in the kitchen.

Did you know?

The water behind a beef burger isn’t just what the cow drank. It also includes the water used to grow the food the cow ate, like grass watered by rain or corn watered from a tap. This is why water footprints are not only about how much water is used, but also about the type of water: green, blue, or grey.

Green, blue, and grey water: what’s the difference?

There are three types of water behind everything we eat:45

- Green water is rainwater absorbed by plants, like the grass a cow eats.

- Blue water is fresh water from rivers, lakes, or underground, used for growing feed, cleaning, or for animals to drink.

- Grey water is about pollution. But it’s not how much water gets polluted, it’s the amount of water needed to dilute the polluted water until it’s considered safe again.

Let's see what this means for some some common foods.

Apples don't need much water. But they create quite a bit of grey water, linked to pollution:

- Green water 68%

- Blue water 16%

- Grey Water 15%

Eggs need a medium amount of water:

- Green water 79%

- Blue water 7%

- Grey water 13%

Beef needs a lot of water. But most of the water is green (coming from the rain):

- Green water 94%

- Blue water 4%

- Grey water 3%

(Did you notice that some of these don't add up to 100%? Well spotted! That's because we're using best estimates).

So, why does our food need so much water?

First, plants need water to grow

Everything we eat starts with growing something, usually a plant. Fruits, vegetables, grains, and even the food animals eat all begin in the soil, soaking up water to grow. Most of the time, plants get what they need from rainwater, which we call green water. But in dry areas or during long, hot summers, farmers might also use water from rivers, lakes, or deep underground to keep their crops healthy. (That’s blue water, if you need a reminder.)

Next, animals need water too

If you’re eating meat, dairy, or eggs, there’s a bit more water involved in getting that food to your plate. Animals need water to drink, just like we do, and they also eat plants like grass, corn, or soy, which need water to grow. Farmers use water to keep barns clean, animals comfortable, and everything running smoothly.

Then there’s the water used after harvesting

Washing, cooking, and packaging food takes water, too. You have to add water to wood pulp before you can press it into sheets of cardboard.6 Plastic needs water to cool it down once it has been shaped into packaging.7 Factories and equipment require regular cleaning. All of this adds to the total water footprint.

Ultra-processed foods (UPF) often use even more water overall

This is because they require many production steps—growing lots of different ingredients, processing them, packaging, and transporting—each of which adds to their total water use. So, choosing whole foods over UPF not only benefits your health but can also help save water.

We can’t forget water pollution

Millions of farmers use chemicals like fertilisers and pesticides to help crops grow and protect them from insects and diseases. These can help us grow enough food. But when it rains, they often wash off fields and into rivers or streams, polluting the water. Even natural fertilisers like manure can cause pollution this way.89 The water needed to clean up that pollution and make the water safe again is called grey water.

Generalisations are helpful, but not perfect

Every food is unique, and the same food can use a different amount of water depending on where and how it was farmed. But there are a few generalisations we can make. For example, fruits and vegetables usually need much less water than animal products.

Meat—especially beef—uses a lot of water. But not all that water comes from the tap. For pasture-raised beef, most of it comes from rain that helps the grass grow. So when you hear that it takes 1,753 litres of water to produce a portion of beef, that doesn’t mean all of it was taken from rivers or drinking water supplies.10

Crops like avocados need a lot of water. Growing them in dry places puts extra pressure on local rivers and underground water, sometimes drying them up. This hurts communities, wildlife, and other farmers. Avocados grow best in wetter tropical areas, where they won’t have such an impact thanks to plenty of rainfall.

Which foods are thirstiest?

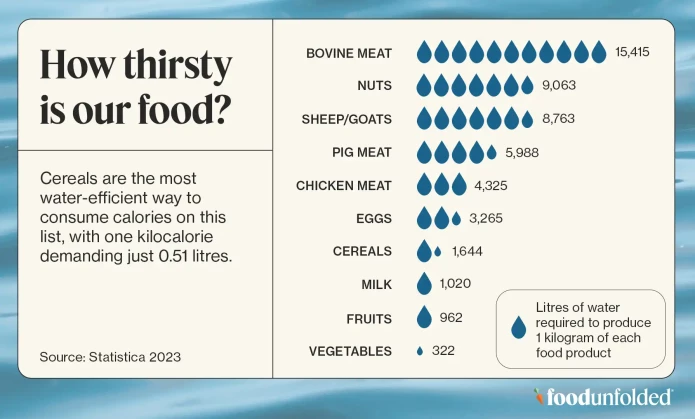

Even though the green, blue, and grey water categories can help us understand why our food needs so much water, the big picture is clear. Some foods are a lot thirstier than others:11

Take beef, for example. Producing just 1 kilogram can use around 15,000 litres of water. That’s more than 200 bathtubs for a single kilo!

Eggs and chicken sit somewhere in the middle. They generally use less water than beef, nuts, or meats like lamb, goat, and pork, but still more than fruits, vegetables, milk, or grains.

At the lower end of the scale are foods like lentils, potatoes, carrots, and seasonal fruits and vegetables, which tend to have a significantly lighter water footprint overall.

What can you do? Everyday tips that make a difference

If you’d like to lower the water footprint of your food, there are six simple steps you can try. It’s not about being perfect or following strict rules. Just making thoughtful choices when you can really adds up. These changes are often good for your health and sometimes easier on your wallet too. The idea is to do what feels possible and sustainable for you.

Plant-powered plates

Eating more plants like vegetables, fruits, beans, and grains usually means using less water than eating a lot of meat and dairy. Plants need water to grow, but they generally use much less than animals do.

Tip: Instead of serving a whole chicken breast per person, you could try using half as much meat and mixing it into a big stir-fry with vegetables and noodles. You’ll still get the flavour and some protein, but with a lighter water footprint and added vitamins and fibre.

Animals from outside

If you do eat meat, dairy, or eggs, choosing products from animals raised outdoors on pasture can help protect water resources. These animals mainly eat grass grown by rainwater rather than crops that need extra irrigation

Tip: there’s no universal “pasture-raised” label to go on meat or animal products in Europe. But you can look out for organic versions, which require animals to have outdoor access during grazing season whenever possible. Whether you shop at a farm shop, butcher, or meat section of the supermarket, you can ask whether any of the products come from animals raised outside.

Whole foods

Choosing whole, minimally processed foods means less water goes into packaging, processing, and transporting. Fresh vegetables, whole grains, and simple snacks often have a smaller water footprint than highly processed foods like chips or ready meals, and they’re often healthier, too!

Reducing food waste

Throwing away food also means throwing away all the water it took to grow, harvest, and transport it. But if you sometimes struggle to use everything up, you're definitely not alone. Most food waste in Europe actually happens in our own kitchens, not on farms or in supermarkets. A few small changes at home can make a big difference for the planet.

Tip: storing food properly in the fridge can make a big difference. Using the right shelf and setting the temperature correctly could do a lot of the work for you. Find out more in this guide to fridge storage.

Imperfectly organic

Organic farming avoids synthetic pesticides and fertilisers that can pollute water and harm nature. While it doesn’t always save water, it helps keep water cleaner and supports healthier soil, which can improve water management. Organic food can cost more, and sometimes organic farms need more land to grow the same amount of crops. It’s not perfect, but it can be a helpful step toward better farming that supports ecosystem health.

Tip: Keep an eye on what's in season to help make buying organic more affordable. Seasonal organic produce is often cheaper because it’s more abundant and hasn’t been shipped far.

Eat Local and seasonal

Buying local food supports nearby farmers and helps protect water resources, especially when we choose foods that grow well in our region and season. In Europe, that might mean apples and root vegetables in the cooler months, grains in harvest season, or fresh leafy greens in spring and summer. Of course, we don’t grow everything locally (you won’t find coconuts from Germany or mangos from Sweden!). It’s all about balance: enjoying global flavours while leaning into local, seasonal options whenever you can.

Tip: As well as reducing meat overall, choosing local meat and dairy can make a big difference to our water footprint. Thanks to our wetter climate, many European farms use rainfed pasture instead of irrigated feed crops.

Final thoughts

Every meal is the result of an incredible journey of water, from the rain that falls to the ground, to the streams and rivers that feed forests and farms, and back again into the sky as clouds. Thinking about this amazing global cycle helps us appreciate water with every bite we take.

In this article, we discussed and explored what is meant by the term ‘water footprint’. We also discovered just how much water goes into producing the food on our plates, looking at which foods are the thirstiest. It seems clear that by making more conscious choices, such as eating more plant-based meals, reducing food waste, and supporting sustainable farming, we can play a part in protecting this vital resource - even at an individual level.

Our food choices are an opportunity to honour the journey of water and help ensure there’s enough to go around for people, ecosystems, and future generations.

Most viewed

My week of AI meal prep: can ChatGPT be a personal chef and nutritionist?

What happens when a computer plans our meals?

Why we crave carbs in autumn and how to stay satisfied

Shorter days can trigger carb cravings. Find out how to stay satisfied and support your mood through winter.

References

- Water Footprint Calculator. (2025). Water footprint of food guide. EcoRise. Retrieved 27/6/25 from

- Water Footprint Calculator. (2025). Water footprints 101: Your direct and virtual water use. EcoRise. Retrieved 27/6/25 from

- Water Footprint Calculator. (2025, June 27). Water in your food. EcoRise. Retrieved 27/6/25 from

- Hoekstra, A. Y., & Mekonnen, M. M. (2012). The water footprint of humanity. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, 109(9), 3232-3237.

- Harris, F., Moss, C., Joy, E. J., Quinn, R., Scheelbeek, P. F., Dangour, A. D., & Green, R. (2020). The water footprint of diets: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Advances in Nutrition, 11(2), 375-386.

- MM Group. (2012). Cartonboard production. Retrieved 27/6/25 from

- British Plastics Federation. (n.d.). How is plastic made? A simple step-by-step explanation. Retrieved 27/6/25 from

- Rodale Institute. (n.d.). Water pollution. Retrieved 27/6/25 from

- Wiederholt, R., & Johnson, B. (2022, August). Environmental Implications of Excess Fertilizer and Manure on Water Quality (Publication No. NM1281). North Dakota State University Extension Service.

- Sachs, J. D., & Schmidt-Traub, G. (2018). Reducing food's environmental impacts through producers' self-monitoring. Science, 360(6392), 987–988.

- Water Footprint Calculator. (2022, July 15). Water friendly food choices. EcoRise.

Do you care about thefood system?

Take part in our Annual Survey 2025

Take the survey