Strawberries feel timeless, don’t they? Whether on top of a summer tart, dipped in chocolate, or eaten straight from the box, these red, juicy fruits are a favourite in gardens and supermarkets across Europe. But the strawberries we know today—big, sweet, and perfectly red—aren’t as old as you might think.

In fact, their story involves espionage, cross-continental travel, and a surprising twist of botanical luck. Behind their sweet, familiar taste is a story of biodiversity and plant breeding. It's also about the tricky balance between flavour and sustainability. So, how did we get from tiny wild berries to the supermarket strawberries we eat today?

Let’s start at the beginning.

Wild origins: where strawberries came from

Before there were fields of strawberries stretching across Europe, there were forest floors. The oldest strawberry species eaten by people in Europe is the woodland strawberry, or Fragaria vesca. Found across much of the continent, especially in central and northern regions, these small, heart-shaped berries were prized in Roman times for their scent and medicinal properties rather than their size or sweetness.

Wild strawberries grow naturally in many parts of the world—Europe, Asia, and the Americas—and for centuries they were gathered rather than cultivated. In 14th-century France, strawberries were grown in gardens more for their beauty than for fruit production. These early berries were delicate, often inconsistent in size and flavour, and available only in season.1

Yet these tiny fruits captured people’s attention. Kings, poets and painters admired them. Even King Henry VIII of England had strawberries growing in his royal gardens. But the strawberries he enjoyed were nothing like the plump red ones you’ll find today.1 2

The oldest strawberry species eaten by people in Europe is the woodland strawberry, or Fragaria vesca.

How strawberries crossed continents

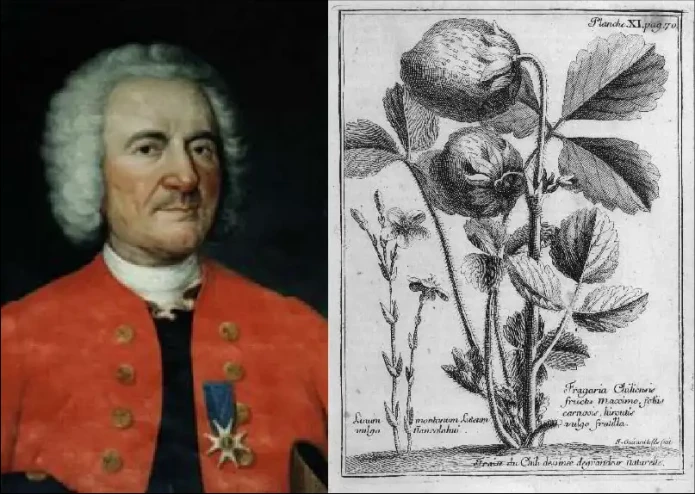

Fast forward to 1712. A French army engineer named Amédée-François Frézier was sent on a secret mission by King Louis XIV. His task? To gather intelligence on Spanish fortifications along the Pacific coast of South America.

While in Chile, Frézier came across something unexpected: large, pale strawberries growing near the coastal city of Concepción. They were unlike any he had seen in Europe. In his journals, he described them like this:

“They plant whole fields with a sort of strawberry rushes… The fruit is generally as big as a walnut, and sometimes as a hen's egg, of a whitish red, and somewhat less delicious of taste than our wood strawberries.”

This was Fragaria chiloensis—the Chilean strawberry. Its fruit was much larger and tougher than European varieties, though not as sweet. Frézier was so intrigued that, when he returned to France, he brought back five plants.1

“They plant whole fields with a sort of strawberry rushes… The fruit is generally as big as a walnut, and sometimes as a hen's egg, of a whitish red, and somewhat less delicious of taste than our wood strawberries.”

— Amédée-François Frézier on the Fragaria chiloensis

But they didn’t do well in the cooler European climate. The plants survived, but barely. It looked like this foreign berry might not adapt after all.2

Then came a stroke of luck.

The birth of the modern berry

Nearby in France, gardeners were also growing a North American species called Fragaria virginiana. This strawberry, brought back from the eastern parts of North America, was much smaller than the Chilean one, but it had excellent flavour and could handle European climates.

At some point—whether by chance or careful cultivation—F. virginiana and F. chiloensis cross-pollinated. The result was a new plant: Fragaria × ananassa, the first hybrid strawberry. A hybrid is a plant created by crossing two different species to combine their best traits.1

This new strawberry had the size and firm texture of the Chilean variety, and the sweetness and resilience of the Virginian one. By the 1750s, it had spread rapidly across Europe. Gardeners loved it. Farmers began growing it for markets. And over time, plant breeders continued selecting for traits like size, bright red colour, sweetness, and longer shelf life. The modern strawberry was born.3

But something else was happening too.

What is cross-pollination? Cross-pollination happens when two different types of plants share pollen—often with help from wind or insects. It allows for new combinations of traits, which is how the modern strawberry was born.

The cost of perfection

Have you ever noticed how supermarket strawberries often look perfect but sometimes taste... bland?

That’s no accident. Over the last century, strawberry breeding has focused heavily on appearance and shelf life. Berries that are big, bright, and firm enough to travel long distances are easier to sell, last longer in stores, and catch the consumer’s eye—making them more commercially attractive.2

But there’s a trade-off. Many modern varieties have lost some of the flavour, scent, and nutritional richness of their wild ancestors in the process.

Today, most commercial strawberries in Europe come from just a handful of varieties. This kind of genetic uniformity (called monoculture) means all the plants are nearly identical. While this makes farming more predictable (because plants grow and ripen at the same rate, and respond similarly to fertilisers and watering), it also makes crops more vulnerable: if a pest or disease attacks one plant, it can easily spread and destroy the rest, because they all share the same weaknesses.1 2

And that’s not all. Strawberries are a delicate crop, often grown in plastic-covered tunnels for out-of-season harvest, requiring large amounts of water, fertiliser, and pesticides. The environmental footprint of strawberry farming is growing, especially outside their natural seasons.3

What’s on your strawberry? Strawberries often top the list of fruits with the highest pesticide residues (there’s a list called ‘the dirty dozen’ which highlights the fruits and vegetables that tend to carry the highest levels of pesticide residues when grown conventionally according to testing by the Environmental Working Group (EWG)). Because strawberries grow close to the ground and don’t have a protective outer peel, they’re especially exposed. Washing helps—but not all methods work equally well. According to experts at the University of Illinois, rinsing strawberries under cold running water is your best bet. Soaking them in baking soda water can also help remove surface pesticides, though no method removes everything. That’s one reason why some people choose organic strawberries, especially when buying out of season.

The story of the strawberry is also a story about the challenges of modern farming: how we balance yield with taste, shelf life with biodiversity, and profit with the planet.

Wild vs modern strawberries

| Feature | Wild Strawberries (F. vesca) | Modern Strawberries (F. × ananassa) |

| Size | Very small | Large (walnut to egg-sized) |

| Flavour | Rich, intense, aromatic | Often milder, sometimes sweet |

| Texture | Delicate | Firmer, more transportable |

| Growing season | Short, seasonal | Longer, extended with tech |

| Nutritional value | Higher in antioxidants | Lower due to breeding trade-offs |

| Biodiversity | Many wild varieties | Fewer commercial varieties |

What consumers can do

The good news? You can still find strawberries that celebrate biodiversity and flavour. Here’s how:

- Buy local and seasonal. Strawberries taste best (and have a lower environmental impact) when grown near you, in their natural season—usually late spring to early summer in Europe.

- Explore old or wild varieties. Farmers’ markets and pick-your-own farms sometimes grow heritage or alpine strawberries. They’re smaller but often far more flavourful.

- Support sustainable growers. Look for organic or regenerative producers who avoid monoculture and use fewer pesticides.

- Grow your own. Even a small balcony can host a strawberry pot! Some wild varieties thrive in shady spots.

Small steps can help preserve flavour, biodiversity, and the stories behind our food.

Every food has a story

Next time you enjoy strawberries with cream, think of Frézier—our French spy-turned-botanist—and the global journey that shaped the fruit on your plate.

The history of the strawberry reminds us that food isn’t just fuel. It’s history, science, culture, and nature, all rolled into one. Understanding how even familiar fruits are bred, farmed, and selected opens our eyes to the complexity behind our meals—and the choices we can make to shape their future.

References

Do you care about thefood system?

Take part in our Annual Survey 2025

Take the survey