With its low melting point, high density, and excellent conductivity, mercury has several industrial and scientific applications. But the unsafe use of this metal can result in severe health and environmental implications, especially through bioaccumulation in seafood.

Mercury enters the atmosphere and water bodies through a number of human activities and natural processes, such as mining, fossil fuel combustion, volcanic eruptions, and gradual discharge from the earth’s crust.1 Once released, mercury interacts with its environment to form various chemical compounds that can be severely toxic to humans and wildlife.

Why is there mercury in seafood?

Mercury that enters water bodies, particularly oceans, turns into a compound called methylmercury because of biogeochemical conditions in marine water and the action of microorganisms living in water and soil.1 Unlike mercury, methylmercury can bioaccumulate because the organs, tissues, and muscles of living organisms can absorb it. This, in turn, causes biomagnification, meaning that the concentration of methylmercury in an organism increases along with its level in the food chain. With this, higher trophic-level fish such as sharks, swordfish, and some varieties of tuna from contaminated waters often have a high concentration of methylmercury in their bodies. If consumed, this toxic compound is passed on to humans and can cause adverse health effects, including neurological and cardiovascular problems.2 Pregnant women and infants are particularly vulnerable to mercury poisoning from consuming such seafood.2 However, not all populations around the world are at equal risk.

Communities that harvest their own fish from contaminated waters are more likely to suffer from the adverse health effects of methylmercury poisoning. Without the rigorous safety checks that internationally traded seafood often goes through, locally caught mercury-contaminated fish may end up on the plates of unsuspecting consumers, causing them grave harm over their lifetimes.

Both lower-income and higher-income countries contribute to mercury pollution through industrial processes like coal combustion, metal production, and waste incineration. Higher-income nations are likely to have stricter regulations today, but historical industrial activities have contributed to contamination that affects local and global environments.

Mercury poisoning in Minamata Bay

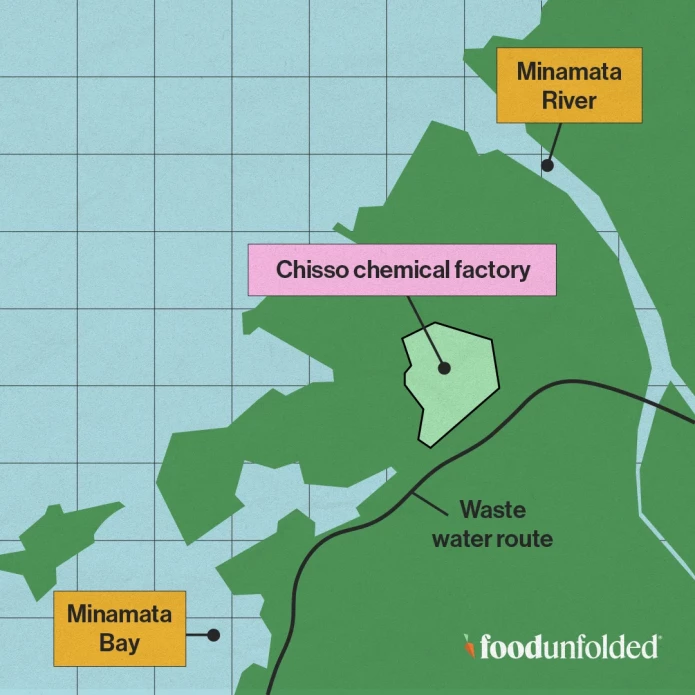

The most infamous case of mercury poisoning occurred in the spring of 1956 when a resident of the Japanese coastal town of Minamata was diagnosed with mercury poisoning from consuming contaminated seafood.

In the years that followed, over 3000 residents were affected by a fatal mercury poisoning disease, which came to be known as the Minamata disease. Chisso Corporation, a chemical company in the vicinity of the town, was found to be responsible for contaminating Minamata Bay and its aquatic life with mercury through its wastewater that flowed into the Bay for 30 years between 1938 and 1968.

The symptoms of Minamata disease include seizures, loss of motor control, and paralysis. The local government took four decades to declare the fish safe to eat. But Minimata isn’t the only place affected by mercury; several other communities face an increased risk of exposure to high levels of mercury poisoning.

Artisanal gold mining communities

An artisanal or small-scale miner is a subsistence miner who independently mines for minerals without being employed by a larger mining corporation. In parts of South America, Africa, and Asia, many communities mine for gold in this way. A common way of extracting gold from the ore is to combine the impure gold with mercury, creating a gold-mercury amalgam. Once extracted, the gold-mercury amalgam is heated to evaporate the mercury.3 While these vapours are extremely harmful to the miners themselves, fish consumers living downstream of mining activities are also at risk because the mercury vapours ultimately end up in water bodies.3

A study investigating mercury exposure in children living close to gold mining sites near rivers in the Amazonian basin concluded that mercury exposure may cause children irreversible physical and mental development impediments.4 In poorer Amazonian communities, such an impediment may dramatically affect children’s ability to pursue secondary education and, later, skilled employment.4 Other studies focusing on mercury exposure near small-scale gold mining sites have highlighted similar situations in Brazil, Peru, Suriname, Côte d'Ivoire, Senegal, Zimbabwe, and Indonesia among others.5,6,7,8,9,10

Hair can accumulate mercury from blood and sweat from the scalp. Because of this, researchers often test hair samples instead of blood or urine when checking mercury exposure in a population.11

Arctic populations

This might surprise many, but the seemingly pristine Arctic is severely affected by mercury pollution.12,13 As much as 32% of the annual mercury deposits in the Arctic are estimated to come from human activity and 64% from re-emissions of legacy deposits.12 Through the atmosphere and water bodies, local fauna such as beluga whales, polar bears, seals, fish, and birds accumulate mercury compounds.13 Most indigenous inhabitants of this region rely on hunting and fishing these animals for sustenance. High levels of mercury pollution in Arctic waters mean that many traditional foods are contaminated, leaving indigenous populations and local wildlife vulnerable to developing irreversible health conditions that impede their quality of life. Due to their dietary habits, Inuit communities are among the most exposed populations in the world.12

Coastal and island populations

Communities native to coastal regions or islands often consume high amounts of seafood. For many smaller coastal communities, fishing is a traditional occupation and fish consumed in the household is often procured directly from the sea. Even without the presence of a chemical factory or mining activities directly contaminating water bodies, coastal waters tend to turn into mercury hotspots because of the global transport of mercury emissions through biomagnification, precipitation, and processes such as evaporation and condensation that are part of the natural water cycle.14 Research conducted to observe mercury levels in people or fish from Vieques in Puerto Rico, Hainan Island in China, coastal regions in Malaysia, Sri Lanka, and Italy, the Bay of Fundy in Canada, and Vologda in Russia, and others, suggest that proximity to the ocean and in turn, higher consumption of seafood, leaves coastal and island populations at higher risk to mercury poisoning and its impacts on health.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21

What is being done to protect vulnerable groups?

Mercury pollution is a globally acknowledged health and environmental issue. In October 2013, 57 years after the first known incidence of the Minamata disease, an international treaty known as the Minamata Convention on Mercury was signed by 137 member countries of the United Nations. This treaty aims to protect human health and the environment from the adverse effects of anthropogenic mercury emissions. Although not exclusively focused on seafood contamination, the convention directs governments to take action to reduce mercury emissions. It aims to provide public authorities access to technical assistance, scientific know-how, and resources for improving public awareness. It also requires involved parties to monitor and report environmental mercury levels. However, not all governments party to the convention are equally equipped to tackle the issue. Mercury hotspots and vulnerable communities are often situated in lower-income regions that need additional resources to combat the problem. While the Minamata Convention is a step in the right direction, it remains to be seen whether the situation of vulnerable communities will sufficiently improve in the years to come.