Fossil fuels touch almost every part of our lives - fuelling our commutes, creating our clothing, powering the lights in our homes, and keeping food on supermarket shelves. But what does a reliance on fossil fuels really mean for our food system?

Beyond human energy and effort across the supply chain, today’s global food system also depends on a different kind of energy - fossil fuels. In fact, the global food system is responsible for at least 15% of worldwide fossil fuel use annually - equivalent to the total emissions from all EU countries and Russia combined.1

This complex dance between food and energy is unsustainable for different reasons. Without radical changes across our food system, we risk failing to stay within the critical 1.5°C target set by the Paris Agreement.2 We are already feeling the implications of a changing climate. But there will be huge consequences for our climate and society if the world’s average surface temperature rises above 1.5C compared to pre-industrial levels, including more extreme weather events, rising sea levels, and loss of biodiversity.3 Beyond environmental sustainability, recent events have highlighted the fragility of this interdependence. The war in Ukraine provides a stark example: during 2022 and 2023, Russia and Ukraine - both major grain exporters - stopped their shipments of grain, cooking oil and fertilisers.4,5 This disruption sent shockwaves through global markets; causing oil prices to spike, which in turn increased transport and fertiliser costs, ultimately resulting in higher food prices around the world.1,6

Addressing fossil fuel dependency in the food system will be key to mitigating climate change and increasing resilience in our supply chains. The Global Alliance for the Future of Food estimates that transforming our food production and consumption patterns could reduce global greenhouse gas emissions by at least 10.3 gigatons a year. That’s 20% of the reduction scientists estimate we need to make to keep within the 1.5°C target of warming set by the Paris Agreement.1

How did our food systems come to rely on fossil fuels?

The reliance on fossil fuels in our food systems dates back to the early 1900s, during the start of the so-called Green Revolution. This period, stretching into the 1980s, saw the introduction of technology into agriculture, which greatly increased crop yields - in some cases, more than doubling them - by bringing in the use of fossil-fuel-based fertilisers, pesticides, and hydrocarbon-fuelled irrigation systems.7,8,9 It is often claimed that the Green Revolution, specifically the development of synthetic nitrogen fertiliser through the Haber-Bosch Process, supported the growth of the global population. The Haber-Bosch Process synthesises ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen gases, allowing for the mass production of nitrogen fertilisers. In fact, by 2008, it was estimated that nearly half of the food produced globally relied on synthetic nitrogen fertilisers.10

Today fertilisers and pesticides are a key part of the global food supply chain, but fossil fuels have also become entrenched in other stages, from packaging and transportation to manufacturing. Fossil fuel use in the food system can be divided into four main stages: Input production, land use and agricultural production, processing and packaging, and retail, consumption and waste.

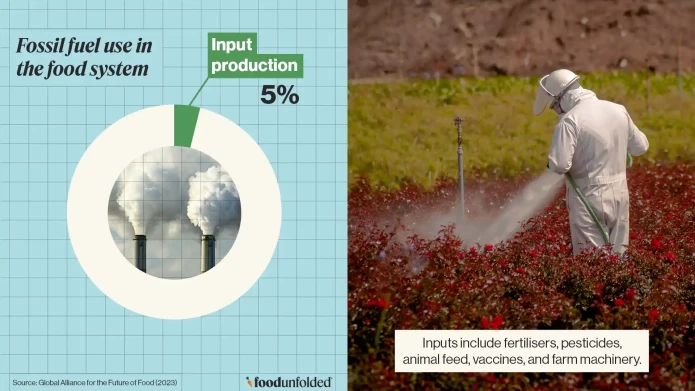

Input production

The production of inputs - fertilisers, pesticides, animal feed, vaccines, farm machinery, plastics and equipment - accounts for around 5% of fossil fuel use in the food system. Most of this is used to produce fertilisers, particularly synthetic nitrogen.1 The Haber-Bosch process, which produces synthetic nitrogen fertiliser, is energy-intensive, requiring high temperatures and pressure to catalyse a reaction between hydrogen and nitrogen molecules.11 This process releases an estimated 450 million tons of carbon dioxide annually - equivalent to the total energy system emissions of South Africa.12

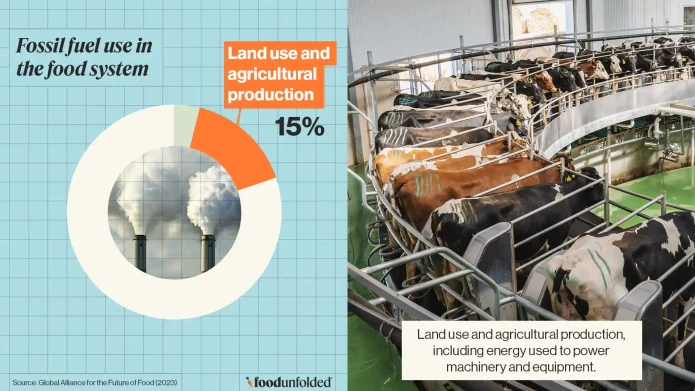

Land use and agricultural production

Land use and agricultural production, including energy used to power machinery and equipment, ventilation, greenhouse heating, fertiliser distribution systems, feed production, animal housing and drying the harvest, accounts for around 15% of fossil fuel (or energy) use in the food system.1

Processing and packaging

Processing and packaging, including all energy used in warehousing, plastic production, transport, refrigeration and processing of ultra-processed foods, accounts for around 42% of fossil fuel use in the food system.1 This stage is particularly energy-intensive due to its reliance on energy-intensive processes such as refrigeration systems, transport and packaging manufacturing. This is one area where fossil fuel use is expected to increase - as the food system becomes more globalised, products will travel further, need better packaging to keep them fresh and face stricter processing requirements, all of which are likely to require more fuel.2

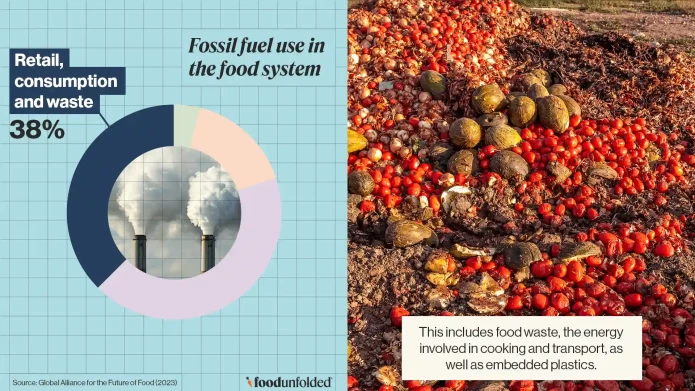

Retail, consumption and waste

Retail, consumption and waste account for around 38% of fossil fuel use in the food system.1 This includes food waste, the energy involved in cooking and transport, as well as embedded plastics. In higher-income countries, the energy intensity of retail is particularly high due to the prevalence of refrigerated containers and factory-processed food.2 Similarly, as consumption patterns have shifted towards eating seasonal crops all year round, food supply chains have become longer, requiring more energy for transport, increasing emissions.

Our food system also produces energy

Paradoxically, our food system both consumes fossil fuels and produces energy that can substitute for fossil fuels. Biofuels like corn and maize, biomaterials such as livestock manure and edible food waste, and on-farm energy sources like small-scale hydropower and solar farming all contribute to this energy cycle.1

It is important to note that this double-edged energy sword has its challenges. One is that biofuel and biomaterial production takes land away from food production.1 This change in land use patterns ultimately increases greenhouse gas emissions, puts pressure on water resources, contributes to air and water pollution and can increase food costs due to scarcity.1,13 Another issue is that policies encouraging biofuel production, such as tax credits, subsidies and loans can lead to deforestation to make way for new plantations. A 2021 report highlighted that EU efforts to boost biofuel production resulted in deforestation, especially in Southeast Asia and South America, of an area equivalent to the size of the Netherlands.14

Are fossil fuels becoming more or less important in our food systems?

Global food demand is set to increase globally by between 35% and 56% by 2050, and the demand for fossil fuels is expected to follow suit.1 Professor Jem Woods, Director of the Centre for Environmental Policy at Imperial College London, expects that “we are likely to see an increased demand for nitrogen fertilisers the world over as countries struggle to maintain and improve food security.” He added: “There is also likely to be greater levels of mechanisation of agriculture in places like Africa, so interest in fossil fuels in agriculture is likely to continue to rise without viable alternatives being put in place.”

“...at the moment, I don’t see fossil fuel use getting any less intense without transformative action throughout food supply chains.” - Professor Jem Woods

He also told FoodUnfolded: “The good news is there are exciting alternatives to fossil fuels such as electrification using renewable energy sources like solar energy and hydro, and then there are other less carbon-intensive ways to capture nitrogen, but at the moment, I don’t see fossil fuel use getting any less intense without transformative action throughout food supply chains.”

This growth in fossil fuel use in the food system is already happening as farming becomes more mechanised and reliant on fossil fuel-based inputs like synthetic fertilisers and pesticides. Supply chains are stretching further across the globe, and the demand for meat, dairy, and ultra-processed foods is rising.2 Moreover, the fossil fuel industry is already making efforts to sustain, or increase, that growth by investing heavily in petrochemicals, which are crucial for food-related plastics and fertilisers, which together, account for around 40% of petrochemical products.1 Between 2016 and 2023, the US planned investments of more than $164 billion in the fossil fuel industry.1

Is fossil-fueled food part of climate action plans?

For the first time, the global food system was mentioned in a climate conference text at COP28 in Dubai in November 2023.15,16 The conference opened with a declaration by 130 countries on sustainable agriculture and included a day dedicated to discussions on food and agriculture. The conference also saw a food road map laid out by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO).17 But while food systems had a bigger role at COP than ever before, critics argue that the language around food in the final text did not go far enough, focussing primarily on adaptation rather than mitigation.16 Adaptation focuses on adjusting to the effects of climate change, while mitigation seeks to reduce the causes of climate change.18

The food system will feature at COP29, which is being held in Baku, Azerbaijan, in November 2024, in the Food, Agriculture and Water Day on November 19th. The negotiations are expected to include talks on reducing methane emissions from organic waste and “build on momentum and commit to coherent and collective action on climate and agriculture issues”.19 It is not yet clear what the talks will entail or what agreements will be signed as a result, however, we know our food system is deeply intertwined fossil fuels, and that solutions are needed at every stage from production to consumption. Without solutions, our food system’s reliance on fossil fuels will continue to threaten our ability to meet the 1.5°C target set by the Paris Agreement.

To learn more about regenerative agriculture, you can watch our documentary and read policy suggestions from grass-root organisations like The European Alliance for Regenerative Farming.