Industrial Agriculture is a leading driver of climate destabilisation and biodiversity loss. But with cropland and pasture covering 38% of land globally, farmland could offer some key solutions to both ecological crises.

In an increasingly developed world, wild animals need all the help they can get as their habitats dwindle. Among the most impacted by our activities on the land are mammals - the (often) furry creatures that would have once called the now-farmlands home. Driven largely by agricultural activities and a resultant loss of habitat, around one-quarter of mammals are currently threatened with extinction, offering just a glimpse at the biodiversity crisis that threatens both future food security and ecosystems around the world.1,2,3

However, by changing land management practices, agriculture can support nearly the same number and diversity of mammals as undisturbed areas.4 And while it’s critical to protect food security and prevent agricultural sprawl, diversification methods don’t have to lead to a reduction in yields.

Here are a few ways sustainable agriculture can help our closest relatives, as well as improving food security, and boosting farmer incomes.

Replanting hedgerows

Hedgerows — rows of trees, shrubs, and plants — are a traditional feature of many landscapes. It can be easy to overlook these staples of rural Britain, Ireland, France, Italy, Finland, and the Iberian Peninsula, but that patchwork of verdant lines provides multiple benefits.5 Hedgerows supply food and shelter to a variety of wildlife, including bats, hedgehogs, voles, mice, birds, and invertebrates.6 Chock-full of plant biodiversity, they also act as ecological corridors, helping animals move across the landscape.7

Left: Hedges being replanted through a government funded scheme in Staffordshire, England. Right: Hedgerows enclose cropland in Somerset. Photos via Getty.

Besides helping animals, hedgerows can benefit farmers too. Planting hedgerows along fields can prevent soil erosion and reduce crop damage from strong winds and the need for pesticides as predatory insects thrive in the vegetation and prey on pest species.10 They also provide shelter and shade for livestock and mitigate flooding, among a long list of other benefits. However, it’s not clear how hedgerows impact crop yields. The charity Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE) commissioned the Organic Research Centre (ORC) to investigate this. The study showed an increase in crop yields of up to 10%, thanks to the various benefits which they provide to the farm ecosystem, but the overall impact can depend on the local context and crops being produced.11 A lack of practical skills, funding and government subsidies can discourage farmers from planting and maintaining hedgerows - but the tide may now be changing.

Farmers are pushing to increase England’s hedgerows by 40% by 2050, while the French government is planning to create 7,000 km of new hedgerows.12,13 The British government’s new environment land management schemes include incentives to maintain and manage hedgerows, while nongovernmental organisations like Woodland Trust also provide grants for hedgerows.14,15 They’re also gaining popularity across the pond, in places like the agricultural fields of California where over 320 km of hedgerows have been planted since the mid-1990s.16,17

Hedgerows have been part of British landscapes for over 4,000 years. But since World War II, agricultural intensification has led to the loss of 50% of British hedgerows.8 Similarly, the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) encouraged farmers to maximise their land area by offering subsidies, so a large percentage of these natural strips were taken down in the 1980s.9

Buffer zones

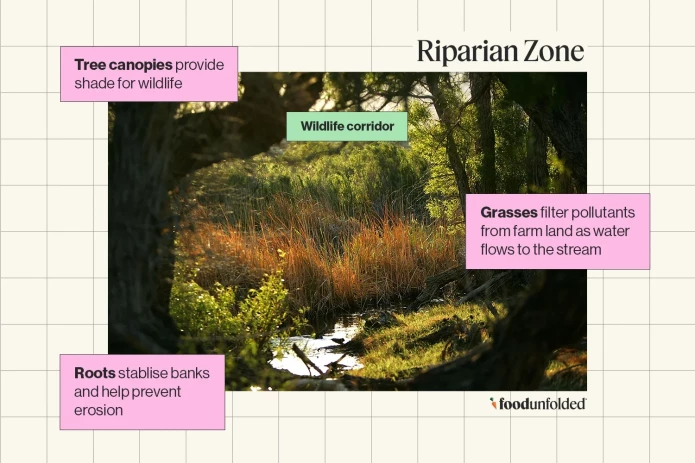

Another agricultural modification that can benefit a variety of animals is buffer zones — or strips of land — around water bodies.18

Buffer zones with native vegetation improve the habitat for mammals like otters, water voles, water shrews, and beavers. For instance, buffer vegetation stabilises stream banks, while its soils filter and purify contaminants from agricultural runoff. Riparian trees reduce and regulate water temperatures and also sequester carbon. At the same time, as water slows down and absorbs into the buffer zone, the watershed can be better protected from droughts and floods.18,19

“The whole riparian area acts as travel corridors for different species, whether they are birds, mammals, amphibians, or reptiles,” Brian Jennings, a Fish and Wildlife Biologist at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, told Food Unfolded.

Maintaining these zones is not only beneficial to mammals but also to freshwater species in the local water bodies, as well as those further out to sea. This is particularly important as less than half of Europe’s water bodies have ‘good’ ecological status and, according to the WWF’s Living Planet Report, freshwater species have seen the highest population declines compared to any other species.20,21

There are however a few hindrances keeping the adoption of buffers down. While buffers are good for the environment, farmers may resist giving up otherwise arable and profitable land, explained Jennings. Additionally, forested buffers can potentially interfere with irrigation systems, while shading could impact nearby crops.

Inconsistent policy frameworks add another challenge for farmers. As it stands, Europe lacks a coherent policy for sustainably managing riparian zones, and they’re not integrated into other policies like the European Union’s Water Framework Directive or Floods Directive.22 It’s also unclear how farmers can receive compensation for maintaining riparian zones under the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy. In order for farmers to create more buffer zones, they would need access to training and technical assistance, along with clear incentives to plant and maintain these zones.

Some governments have pushed ahead with their own policies. For instance, Denmark established 10-metre buffer zones for all streams and lakes over 100 square metres in 2012.23

Adding trees to agriculture

The ancient rooted practice of agroforestry, where trees and shrubs are incorporated into crops and livestock fields, is another way to improve the biodiversity of farm fields. For instance, in Portugal, the Montado landscape, marked by oak trees, grazing animals, and crops, dates back 14 centuries.24 However, many European agroforestry systems have suffered the same fate as hedgerows — disappearing over the last century due to agricultural mechanisation and intensification that favours a more simplistic monoculture approach to farming.

Watch Resilient farms in Germany to learn more about agroforestry.

Bulls graze on a pasture where trees have also been planted in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Agroforestry is the name given to this combination, in which trees or shrubs are used in fields or arable farming and animal husbandry are combined. Photos via Getty.

Still, this traditional practice offers a genuine solution for declining biodiversity, supporting higher levels of mammalian diversity than land under pure forestry or intensive agriculture.25 In addition, agroforestry benefits insect pollinator health, native earthworms, improves water quality and soil biodiversity, and stores carbon.26,27

Farmers can also profit directly from these systems, especially in a longer term scenario. Agroforestry can increase the productivity of agricultural lands by between 14% and 100%, effectively reducing the need for land expansion and added resources.28,29 It also protects crops and livestock from extreme weather - something we can expect as climate change increases the severity and unpredictability of extreme weather events. Finally, timber products provide a long-term alternative source of income for farmers, diversifying the funding and offering farmers an economic safety net to supplement crops.

However, despite this impressive array of benefits, a lack of advice on establishing and managing these systems continues to deter many farmers. There are also high costs associated with implementing agroforestry systems and the increased labour for its management can be a hindrance in itself. Nonetheless, there is increasing recognition that agroforestry practices increase agricultural resilience in the face of climate change, and financial support for these systems is now available in the EU through the Common Agricultural Policy’s subsidy and support frameworks.30

Rethinking our approach

It’s clear that farming does not need to be a one sided affair. Simply by changing how we feed the world, farming can help biodiversity recover while maintaining crop yields to support a growing population. To do this, farmers will need clear and coherent policy to support their transition to nature-friendly farming methods. And this shift requires financial assistance for both implementing and maintaining these systems, along with technical support, tools, and training. It may sound a lot to ask. But for the sake of our future food security, biodiversity, and the people who reap the joys of encountering wildlife as they work and play in rural places, it’s well worth the investment.

To learn more about regenerative agriculture, you can watch our documentary and read policy suggestions from grass-root organisations like The European Alliance for Regenerative Farming.